Before there was alleged crypto scamster Sam Bankman-Fried, the harrowing Ponzi scheme of Bernie Madoff and the rapacious Wolf of Wall Street, Jordan Belfort, there was Michael Milken.

If you’re old enough to remember, Milken symbolized the so-called “decade of greed,” a slander perpetuated by the left during the 1980s boom. From his perch at the now-defunct Drexel Burnham Lambert, Milken’s creative use of so-called junk bonds financed a wave of buyouts and led to unmatched Wall Street corruption that destroyed jobs, upended once-great companies and ate at the moral fabric of the nation’s soul.

It’s almost all a lie, of course. The 1980s were a period of unmatched growth thanks to Reaganomics that cut taxes and regulations so successfully that the economic team of Bill Clinton no less emulated such “supply side” methods to keep the Reagan revolution rolling for years. Milken himself deserves accolades for propelling Reagan-era prosperity.

Sure, his use of high-yield junk-bond debt helped fuel the buyout mania of the time. It also enraged the financial establishment as scores of companies that were denied financing turned to Milken and Drexel to grow and prosper. Don’t believe me. Just ask the executives who built empires on Milken’s financial acumen, Ted Turner, John Malone and Rupert Murdoch (my ultimate boss), and many more.

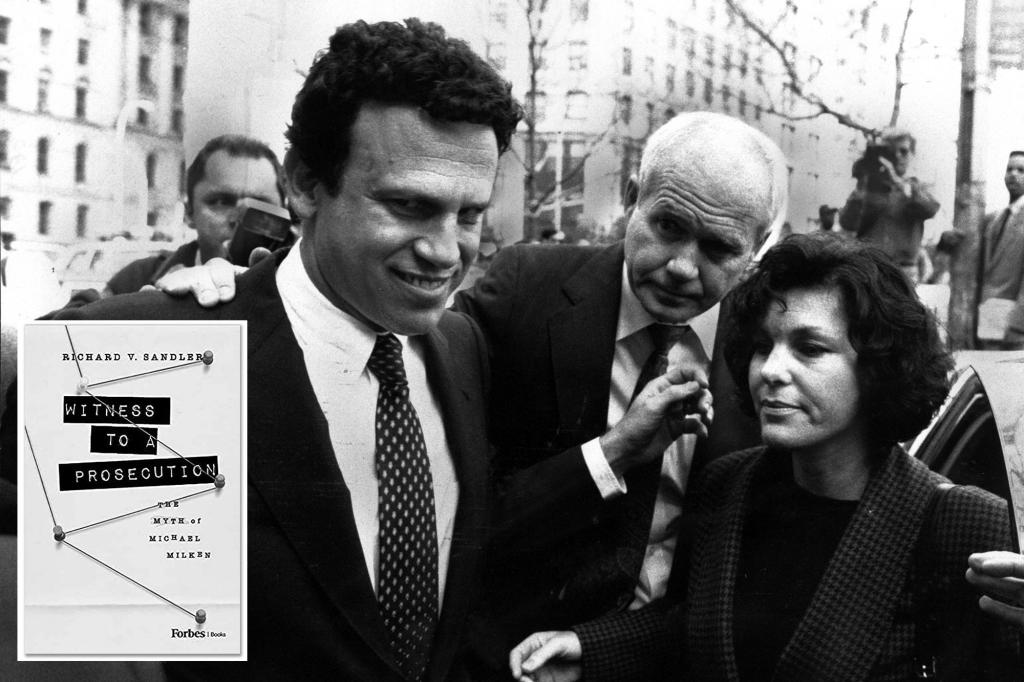

Richard V. Sandler’s new book, “Witness to a Prosecution: The Myth of Michael Milken,” goes far in debunking another lie: That Milken was the era’s Bernie Madoff. The book shows convincingly how prosecutors spun a series of low-level infractions and book-keeping errors into securities fraud and the crime of the century. They did it to advance their political careers and feed the blood lust of a media looking to make Milken a symbol of that greedy decade. They were assisted by a Wall Street establishment Milken was crushing in the financial arena.

Or in Sandler’s words, “The nature of prosecution and the technicality and uniqueness of the regulatory violations certainly never would have been pursued had Michael not been so successful in disrupting the traditional way business was done on Wall Street.”

Renaissance

Decades have passed since the spectacle of Milken’s prosecution under the flamboyant then-US Attorney for the Southern District, Rudy Giuliani, and Milken’s ultimate conviction. Milken has been out of prison for 30 years, enjoying a renaissance rarely afforded to people polite society deem white-collar crooks, and for good reasons, Sandler points out.

He runs the eponymous think-tank Milken Institute, where thought leaders from industry, government and academia flock to his conferences. (Full disclosure: I’m an occasional unpaid panel moderator.) He’s a prostate-cancer survivor and has dedicated himself to its research, one of the big reasons this once deadly disease is manageable. (Another full disclosure: I’m a survivor as well, thus a beneficiary of Milken’s efforts.)

Milken’s rehabilitation was no easy feat, and Sandler has a unique, albeit biased perch as a “witness” to this resurgence. He was one of Milken’s lawyers during those tumultuous times and remains so today. The two are childhood friends. OK, he’s pretty biased. But what Sandler does, masterfully in my opinion, is tell his story through the prism of some of the top prosecutors in the case, John Carroll, who worked for Giuliani, and Bill McLucas, who was part of the enforcement division at the Securities and Exchange Commission.

Neither called the Milken prosecution a mistake, mind you, yet years later as they look back with the benefit of time and experience, both appear to downplay the seriousness of his transgressions. As McLucas put it, “The government, generally speaking, was probably more aggressive in my view because Drexel and Milken were not as bad as they were perceived to be . . . You don’t get rewarded for never bringing a case.”

Yes, scary stuff if he’s quoting them accurately, and Sandler is too careful of an attorney not to. Quotes like this help make Sandler’s case that Milken’s punishment didn’t fit the crimes he was accused of or even what he ultimately pleaded to: Six instances of guilt with no insider trading. Ivan Boesky, the notorious insider trader, turned evidence against Milken to get a reduced prison term for his own, more sweeping fraud. Yet his accusations that Milken committed insider trading on deals between the two never made it into the plea agreement.

Milken was initially sentenced to 10 years in prison amid the media scrum; it was later reduced to just around two when cooler heads prevailed. Most damning in my view is Sandler’s rebuke of white-collar law enforcement. It’s obsessed with cases that bring media acclaim, with ambitious prosecutors unwilling to walk away from their draconian pursuit of justice. I couldn’t help but be reminded of the travails of former Wall Street investment banker Frank Quattrone, who faced years in jail for an email that could be interpreted 50 different ways but that the feds and the media contrived as evidence of obstruction. (Quattrone’s conviction was later reversed.)

I would say Sandler is on the weakest ground providing just one side of the Milken story. The book reads at times like a legal brief for the defense. Journalism is about providing both sides. “Witness to a Prosecution” would have benefitted from an interview with Giuliani, whom Sandler derides for his “use of raw power to gain publicity” and advance his political career as a successful mayor of NYC and a not-so-successful run for president. (Giuliani advocated for a pardon of Milken that President Trump granted in 2020.)

That said, this book should be required reading for law schools preparing the next generation of prosecutors who think the stepping stone to fame and fortune is to crush one of the great financial minds of our time.

𝗖𝗿𝗲𝗱𝗶𝘁𝘀, 𝗖𝗼𝗽𝘆𝗿𝗶𝗴𝗵𝘁 & 𝗖𝗼𝘂𝗿𝘁𝗲𝘀𝘆: nypost.com

𝗙𝗼𝗿 𝗮𝗻𝘆 𝗰𝗼𝗺𝗽𝗹𝗮𝗶𝗻𝘁𝘀 𝗿𝗲𝗴𝗮𝗿𝗱𝗶𝗻𝗴 𝗗𝗠𝗖𝗔,

𝗣𝗹𝗲𝗮𝘀𝗲 𝘀𝗲𝗻𝗱 𝘂𝘀 𝗮𝗻 𝗲𝗺𝗮𝗶𝗹 𝗮𝘁 dmca@enspirers.com