Nobody who watched Alexei Navalny’s meteoric trajectory, from civic activist to opposition chief to the world’s most well-known political prisoner, might keep away from the query: how will this extraordinary saga finish? Was Navalny destined to develop into Russia’s Nelson Mandela, a redemptive chief who guided his folks from oppression to the promised land of democracy? Or was he doomed to be silenced by the henchmen of the despot whose rule he had challenged?

We now know the reply. Earlier than his loss of life in an Arctic jail in February, Navalny additionally contemplated his unsure future. Within the epilogue of his autobiography, Patriot, he recollects a poignant dialog along with his spouse, Yulia, by which each come to phrases with the probability he’ll die in captivity.

But on the similar time, he writes, “there is an inner voice that you can’t stifle: Come off it, the worst is never going to happen.”

Overview: Patriot – Alexei Navalny (Penguin Random Home)

Penguin Random Home

These two doable destinies have left their mark on Navalny’s ebook. The primary half is a candid, usually humorous and self-deprecatory narrative of his life, his activism and the making of his political profession. This part is framed by his stunning 2020 poisoning with the nerve agent novichok, his recuperation in Germany and his subsequent return to Russia.

The second half is a jail diary, interspersed with public statements and his “final words” at trials. As he’s shunted between ever extra hellish outposts of Putin’s penitentiary system, the textual content turns into extra fragmented.

For a lot of months, his sleep was disrupted by hourly inspections as a result of he was an “escape risk”. Later, throughout a protracted stretch in a punishment cell, he endured the unrelenting, blood-curdling screams of his neighbour “the psycho,” a assassin utilized by the administration to torment Navalny.

What lends unity to his ebook is the unwavering consistency of Navalny’s resistance. As a pro-democracy activist, he instigated mass protests that repeatedly shook the foundations of Putin’s dictatorship. As an anti-corruption campaigner, he shone a highlight on the kleptocratic rot that festered behind the patriotic posturing of Kremlin propagandists. As a political prisoner, he demonstrated extraordinary ethical braveness, talking out towards struggle whereas enduring mistreatment that may solely be described as torture.

One signal of Navalny’s enduring significance was the crowds of residents who defied brutal repression to pay their respects at his funeral. One other is the unrelenting torrent of disinformation and vilification now directed towards his reminiscence.

Mourners at Navalny’s funeral in Moscow, below heavy police presence, on March 1, 2024.

AP

The commonest smear is that Navalny was not a freedom fighter, however a far-right nationalist, a Russian imperialist, and a supporter of Putin’s invasion of Ukraine. In 2021 Amnesty Worldwide designated Navalny a prisoner of conscience. In response Kremlin trolling factories unfold accusations that grew to become an article of religion for a vocal group of teachers, commentators, and social media influencers.

Navalny’s autobiography is a vital corrective to the disinformation. It exhibits how his activism was impressed not by nationalist grievances or far-right ideology, however by the teachings of rising up below totalitarianism and by his consciousness as a younger grownup that the historic alternative supplied by the collapse of the Soviet regime was being squandered.

It additionally illuminates features of his internal life overshadowed by his persona on social media. A voracious reader since childhood, Navalny has quite a bit to say about books. His jail diaries are scattered with reflections on literature starting from Soviet-era rebels like Viktor Erofeev to European classics by authors equivalent to Tolstoy, Maupassant and Dickens.

No much less stunning was his unostentatious however sturdy Christian religion. Being a believer, he displays, “makes it easier to live your life and, to an even greater extent, engage in opposition politics.”

From ‘paradise’ to lies

No childhood occasion left a larger impression on Navalny than the Chornobyl catastrophe. Half of his prolonged household was Ukrainian. He used to spend summers at his grandparents’ farm within the village of Zalissiya, remembered as “paradise on earth”, a spot with “a stream and trees laden with cherries”. Right here he was surrounded by crowds of relations who had been “the jolliest, most wonderful people”.

Sadly the village was close to the Chornobyl nuclear energy plant. After the meltdown of the plant’s No.4 reactor on 26 April 1986, Navalny’s pastoral paradise grew to become a radioactive exclusion zone. His relations had been forcibly relocated and scattered throughout Ukraine.

A 1986 aerial view of the Chornobyl nuclear plant exhibiting harm from an explosion and fireplace that despatched massive quantities of radioactive materials into the environment.

Volodymyr Repik

What most affected ten-year-old Alexei was the duplicity of the federal government’s response. As an alternative of warning in regards to the catastrophe, officers tried to hide it, with lies that uncovered numerous folks to deadly radiation. A long time later, this lesson within the risks of mendacious, unaccountable energy formed Navalny’s first impressions of Putin. “He never stops lying,” Navalny recalled, “just as in my childhood”.

In contrast to Putin and most Russian imperialists, Navalny was detached to the breakup of the Soviet empire. What aroused his indignation was the hypocrisy of the “democratic reformers” of the Nineties. As a young person, he had admired Boris Yeltsin, Russia’s first post-Soviet president, however he was slowly disillusioned by pervasive corruption and the rise of the oligarchs.

The turning level was Navalny’s try, as a college scholar, to import an inexpensive automotive from Germany in 1996. After three days spent lining up at a customs workplace, the place everybody else was paying bribes to chop by way of purple tape, he reached the pinnacle of the queue, solely to be told the workplace was closing due to a go to by Yeltsin’s press secretary.

That have, he mirrored,

proved to me one thing that I had been obstinately refusing to confess: Yeltsin’s reign was not about reform […] he was only a sick previous alcoholic with a bunch of cynical fraudsters round him going about their common enterprise of lining their pockets.

Corruption and dictatorship

Navalny pointed to totally different life experiences of Yeltsin, an ex-communist social gathering boss who had dominated the town of Yekaterinburg “like a typical Soviet petty tyrant,” and the previous dissidents who had led “velvet revolutions” in communist East Central Europe.

In contrast to Yeltsin, Poland’s Lech Walesa and the Czech Republic’s Vaclav Havel,

had stood their floor within the face of oppression and persecutions, and over a few years had proven in motion a real dedication to the phrases they proclaimed from the rostrum.

In his personal life, Navalny would develop into an exemplar of that type of defiance, talking reality to energy with out regard for his personal security.

Incensed by the backroom deal that introduced Putin, a corrupt underling with a KGB previous, to energy, Navalny joined the left-liberal Yabloko social gathering in order that “I would be able to tell my grandchildren, ‘I was against it from the outset’.” However as an alternative of vigorous opposition to Russia’s backsliding, Yabloko’s leaders most well-liked backroom offers with Kremlin. The social gathering was worn out within the 2003 Duma elections.

In response to rising media censorship, Navalny grew to become co-organiser of a sequence of political debates in Moscow nightclubs. They had been an amazing success – till the authorities moved to close them down. Bureaucratic harassment and raids by Kremlin-linked neo-nazi gangs meant no venue was ready to host them.

Navalny undertook one other daring experiment, aiming to attract reasonable Russian nationalists into an anti-Putin democratic coalition. “A serious political leader,” he explains, “cannot simply decide to turn their back on a huge number of his fellow citizens because he personally dislikes their views.” The document exhibits that Navalny typically mirrored these views, and typically challenged them.

In 2011, he exhorted the group at a nationalist rally to empathise with the plight of the inhabitants of the Muslim republics of the Russian Caucasus. It was not lengthy earlier than nationalist militants had been complaining that Navalny had by no means been a nationalist, solely a liberal who had used nationalists for his personal ends. One success of that technique was the lively participation of anti-Putin Russian nationalists within the mass protests towards election fraud in 2011-12.

By then, Navalny’s defining trigger had develop into the battle towards corruption. Utilizing his authorized coaching and strategies pioneered by Western shareholder activists, he tried to carry the administration of state-owned oil and gasoline firms accountable for the theft of billions in elaborate corruption schemes. He set out the outcomes of his investigations on a Livejournal weblog that shortly grew to become one of the in style and influential within the nation.

Within the decade that adopted, he prolonged his attain utilizing YouTube, Twitter, Instagram, and even TikTok. What remained fixed was his sensible sense of humour and his unrelenting deal with the interconnection between corruption and dictatorship.

A community of activists

Navalny’s account of his political campaigns presents precious insights into the character of civic activism in authoritarian circumstances. To outdoors observers, he usually seemed to be a superb, solitary hero locked in a lonely battle with a brutal regime. The truth was extra sophisticated.

As he repeatedly emphasises in his ebook, he was indebted to quite a few helpers. Some had been volunteers who responded to his appeals for specialist experience. Others had been activists who joined his Anti Corruption Basis or the branches of his presidential marketing campaign. By the point of his imprisonment, Navalny had created a nationwide community of dedicated activists who represented a critical problem to the soundness of Putin’s sham democracy.

What made Navalny such a risk to Putin’s rule was a succession of protest waves, when lots of bizarre residents adopted him onto the streets to demand change.

Probably the most well-known had been the 2011-12 mass protests towards election fraud, Navalny’s Moscow mayoral marketing campaign (2013), the demonstrations impressed by Navalny’s expose of prime minister Medvedev’s corruption (2017), Navalny’s presidential marketing campaign (2017-18) and protests towards the exclusion of opposition candidates from the Moscow Duma elections (2019).

In more and more authoritarian circumstances, massive numbers of bizarre Russians took actual dangers to specific their rejection of Putin’s path.

Navalny addresses a crowd in Moscow in 2019.

Pavel Golovkin/AAP

What’s tougher to confirm is Navalny’s account of the sources of the Putin regime’s aggression on the world stage. In response to him, the invasion of Ukraine was pushed not by the nationwide curiosity or geopolitics however by the regime’s home wants. The objective was to redirect in style consideration from financial stagnation and lawlessness to imperial hysteria. As Navalny declared in courtroom two days after Putin unleashed full-scale struggle in February 2022:

I contemplate [the war] immoral, fratricidal and legal. It has been began by the Kremlin gang to make it simpler for them to steal.

Certainly, there’s a case to be made that the struggle’s timing was linked to the “Navalny Crisis” that adopted his poisoning in August 2020. This disaster dealt a double blow to the regime’s legitimacy. It uncovered Putin as a tyrant ready to make use of banned chemical weapons to silence his most outstanding political opponent and impressed Navalny’s workforce to supply A Palace for Putin, a two-hour documentary spotlighting the president’s private corruption.

Jail diary

Navalny’s jail diary, which makes up the ultimate a part of the autobiography, constitutes a type of political testomony. It places on document his condemnation of Russia’s struggle towards Ukraine. It units out a imaginative and prescient of a postwar settlement, which incorporates struggle crimes trials, reparations, and the restoration of Ukraine’s 1991 borders.

And it presents a blueprint for a post-Putin Russia, the place the focus of energy in Russia’s “super-presidential” system has been changed by the checks and balances of a parliamentary democracy.

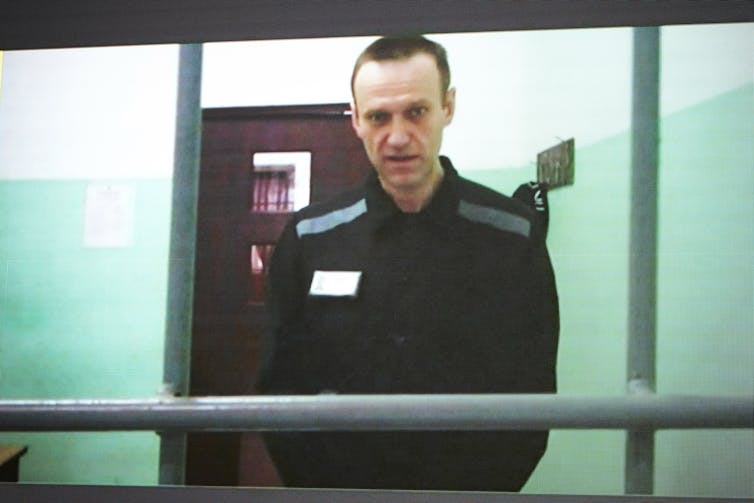

Navalny seems in a video hyperlink from the jail colony in Melekhovo, Vladimir area, throughout a listening to on the Russian Supreme Court docket on June 22, 2023.

Alexander Zemlianichenko/AAP

The diary is a harrowing account of each day life in a penitentiary system that has modified little since Soviet instances.

The bureaucratised cruelty, the acute chilly, the insufficient meals and medical care, the sleep deprivation, the lengthy phrases of solitary confinement, the challenges of coping with informers, would all be acquainted to readers of well-known Soviet-era dissidents like Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, Vladimir Bukovsky, Natan Sharansky, and Anatoly Marchenko.

Like earlier chroniclers of the Gulag, Navalny presents a type of survival guide for future prisoners. He explains his psychological methods for sustaining a starvation strike, and the bodily challenges of rising from it.

He mocks his persecutors, and manages to search out humour or ironic prospects in each try to punish and degrade him. When prosecutors lay one more set of absurd expenses, together with terrorism and rehabilitating Nazism, Navalny derides this indictment with a sardonic boast referencing Sherlock Holmes’ nemesis Professor Moriarty:

I’m a genius of the underworld. Professor Moriarty isn’t any match for me […] hardly ever has a legal finished as a lot on the skin as I’ve finished behind bars.

To maintain up one’s morale in jail, Navalny recommends imagining the worst doable destiny – in his case, disappearing from the lives of family members, lacking youngsters’s commencement ceremonies, by no means seeing grandchildren, dying alone in jail – and accepting it.

He recollects that the Soviet dissident and author Anatoly Marchenko had died throughout a starvation strike in jail in 1986, and a few years later the Soviet Union was gone:

So even the worst doable state of affairs will not be truly all that unhealthy. I resigned myself and settle for it.

It’s unimaginable to know whether or not the Putin regime is already coming into the type of terminal disaster that was unfolding within the USSR in 1986. What is definite is that Navalny’s reminiscence can be an inspiration for generations of Russians who search to reside in a freer, extra democratic society, at peace with its personal folks and the world.

If a democracy emerges from the ashes of Putin’s dictatorship, Navalny can be celebrated as its prophet. His autobiography is destined to develop into the canonical textual content of Russia’s democratic custom.