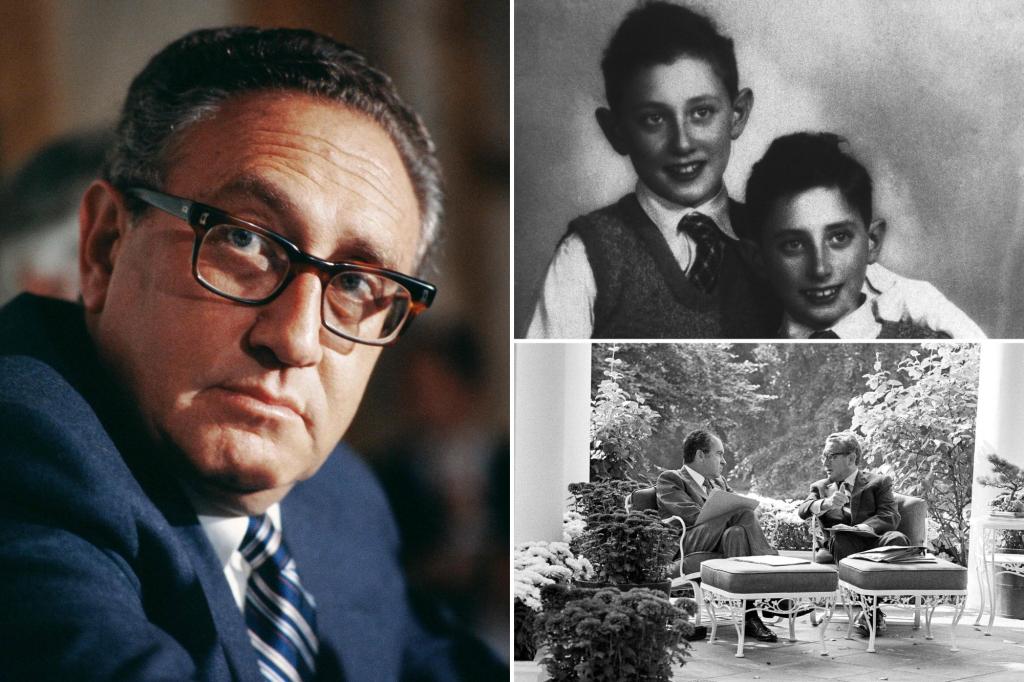

One hundred years ago, Heinz Alfred Kissinger was born in Furth, Germany.

This past week he made headlines throughout the world with his reflections on the shifting geopolitical realities of Central Europe.

It was as if he chose to send the world a centennial birthday greeting that he remains, as he has been for 70 years, an outstandingly lucid and perceptive authority on the strategic balances and constantly shifting correlation of forces between the major powers of the world.

What an astonishing century he has had.

No one could possibly have imagined in Henry Kissinger’s early youth that the European state most accommodating of its Jewish population would a decade later be governed by a genocidally anti-Semitic and totalitarian dictatorship.

When young Kissinger and his parents and his brother, all of whom would live well into their 90s, departed Germany a few months before the infamous Kristallnacht of November 1938, and arrived at New York on the famous liner SS Île de France, it would have been hard to imagine that he would return to Germany in just seven years.

And as a 22-year-old sergeant in the United States Army would be the military governor of a town approximately as large as that, 200 miles away, where he was born.

When Henry Kissinger was in his late teens, working in a New York toothbrush factory and attending school at night and struggling to master English, it would have challenged credulity to think that he would develop an extraordinarily fluent and sophisticated articulation in English, while retaining a German accent so pronounced that he sometimes sounds like one of the Marx brothers imitating Kaiser Wilhelm II.

Early impact

When he launched his academic career, it would have been conceivable but hugely unlikely that within ten years he would achieve such an eminence as a lecturer and as an author in foreign policy matters that he would have a substantial, if not universally approved, influence on the foreign and strategic policy of the greatest power in the world, where he had not long been resident.

This was the impact of his seminal book “Nuclear Weapons and Foreign Policy,” which was brought out in 1957 and suggested the development of median alternatives to the Eisenhower policy of massive retaliation.

Improbable though it was that a young academic fugitive from the Nazis would have such an influence in the United States so soon, it was much more improbable that he would, 15 years later, play a decisive role in negotiating the greatest arms control agreement in the history of the world, one that, incidentally, restored American nuclear superiority.

His first book, “A World Restored” (also issued in 1957), an extraordinarily precocious success as the publication of his Harvard Ph.D. thesis, demonstrated how the Austrian foreign minister and then chancellor for a total of 39 years, Metternich, the convener of the Congress of Vienna that generally stabilized Europe for a century, though he deployed less power by normal measurements than France, Britain, Prussia or Russia, made himself the “Coachman of Europe” for a whole generation.

The ramshackle Habsburg Empire, pulling and pushing an unwieldy congeries of cultures and ethnicities, an incomprehensible “costume party in a decaying country house” as Metternich described it, yet managed by artistically shifting its influence in the center of Europe between the other powers, gave Metternich a profound but subtle influence over all Europe more durable than that achieved by any other statesman.

It would have been difficult to imagine that this recent immigrant and factory worker would, while still in his mid-30s, become the principal foreign policy advisor to the wealthiest family in the world; that he would start writing position papers for Nelson Rockefeller, twice a contender for the Republican presidential nomination, and 15 years later would serve, in an administration with Rockefeller as vice president, as secretary of state.

Understanding power

The only other foreign-born foreign minister of a major power in centuries is Ioannis Kapodistrias, a Greek who between 1816 and 1822 served as Russian foreign minister.

In traditional European great power terms of conducting intricate negotiations closely adapted to particular regional circumstances and leading to important and durable conclusions, Mr. Kissinger’s career is really only comparable to those of Richelieu, Talleyrand, Metternich and Bismarck.

Of those statesmen, Talleyrand was the only one who was not also the head of the government asserting autocratic authority in the name of a comparatively passive monarch.

Mr. Kissinger is the only prominently successful foreign minister of a great power who achieved his office not by politics or the legal profession or the armed forces, but by his academic renown as a historian of power relations and a persuasive public foreign policy advocate.

No one else has been so successful as both an academic foreign policy theoretician and historian and as the foreign minister of a great power.

He and Richard Nixon, the president who brought him into government and with whom he principally served, were entirely different personalities, brought together by their shared knowledge of foreign policy and strategic issues and their aversion to the sluggish groupthink of foreign ministry bureaucracies.

Except for Charles de Gaulle, no comparably important statesman of the last hundred years, not even Winston Churchill who won the Nobel Prize for literature, is as elegant a memoirist and writer of history as Mr. Kissinger, and no prominent statesman except Singapore’s Lee Kuan Yew, has been so durably important entirely because of his personal knowledge and always perceptive and original appreciation of international relations.

Still got it

More than 60 years after he arrived at New York as a fugitive from the Nazi pogroms, Mr. Kissinger was the initial chairman of the commission to investigate the Islamic suicide terrorist attacks of Sept. 11, 2001.

When he was a director of our company, Hollinger Inc., in the 1990s, we filed the SEC director’s form and in the box requiring the occupation of the director, it was always sufficient simply to reprint his name.

Mr. Kissinger’s book “Leadership,” published last year, was of the same high quality of scholarship and style as the book on Metternich published 65 years before.

After he retired from government in 1977, large numbers of government leaders and ministers visiting New York for the UN General Assembly in autumn would call upon him and have continued to call upon him in increasing numbers in all the subsequent years.

Through it all, Mr. Kissinger has had a piercing sense of humor: When asked by a reporter as he arrived at the bar mitzvah of the son of the Israeli ambassador in Washington if it reminded him of his own bar mitzvah in Germany, he instantly replied: “Actually, von Ribbentrop wasn’t able to come to mine.”

Though a number of his successors have been talented secretaries of state and national security advisers, the US has paid a heavy but incalculable price for not recalling him to high office.

Having had the great privilege of being his friend for more than 40 of these hundred years, it is an inexpressible pleasure to wish him continued good health and every happiness and success on his centenary, and to record that he carries into his second century the respect and the good will of the whole world. He will retain it always.

Reprinted with permission from The New York Sun.

𝗖𝗿𝗲𝗱𝗶𝘁𝘀, 𝗖𝗼𝗽𝘆𝗿𝗶𝗴𝗵𝘁 & 𝗖𝗼𝘂𝗿𝘁𝗲𝘀𝘆: nypost.com

𝗙𝗼𝗿 𝗮𝗻𝘆 𝗰𝗼𝗺𝗽𝗹𝗮𝗶𝗻𝘁𝘀 𝗿𝗲𝗴𝗮𝗿𝗱𝗶𝗻𝗴 𝗗𝗠𝗖𝗔,

𝗣𝗹𝗲𝗮𝘀𝗲 𝘀𝗲𝗻𝗱 𝘂𝘀 𝗮𝗻 𝗲𝗺𝗮𝗶𝗹 𝗮𝘁 dmca@enspirers.com